The text

2 Samuel 11-13; Psalm 51

“Against you, you alone, have I sinned, and done what is evil in your sight…” Psalm 51:4a

The text in context

King David

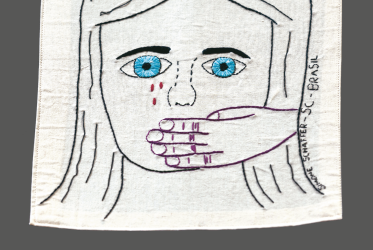

There is silence in David’s house. A silence to be uncovered and interrogated. A silence shielding toxic masculinities shrouding women in shame and blame as rape and violence are committed against their bodies and their children. A silence rendering homes unsafe, while exonerating men of power, privilege, and wealth. David and his sons are complicit in the violence and the silence women experience in the household of this King of Israel who is most often named “a great king”, “a good king,” and “a man of God.

David is an archetype. He is that man for whom power, privilege, and wealth have afforded a reshaping of the narratives of his life. We know him as a deeply spiritual man of God, one who cried to God in lament for the wrongs he had done (Psalm 51). Among the heroes of the biblical narratives, David is generally presented as one most definitely worth emulating. He is recorded and venerated as a great king, a great warrior, a man of faith whose life was defined by his being anointed as king, as well as his legendary childhood battle with the giant Goliath (1 Samuel 17).

He brought the ark of the covenant back to Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6), an act that centralized worship and the presence of God in the lives of the people he ruled. There is a preference for this picture of David rather than the one that emerges from his home and his interactions with the people closest to him – his family and his immediate neighbour. The narratives paint a picture that decries the image of David popularized in the church and preached from the pulpit.

Toxic Masculinities

Beyond the battlefields, where David was successful in battling his enemies, we get a different experience of him. One meets a king who uses “royal power abusively to satisfy his own personal desires.”[1]His relationship with Bathsheba, his neighbour’s wife, is worth scrutiny (1 Samuel 11). He lusted after his neighbour’s wife. A neighbour whose house was so close to his that he saw Bathsheba bathing from the roof of his house. A neighbour who was among his most trusted warriors and was away at war. David wrongs his neighbour and friend, but what ultimately happened is that “David sees a beautiful woman bathing and exercises royal privilege to ‘take her’.”[2] David sent for Bathsheba “and he lay with her” resulting in her pregnancy (2 Samuel 11:1-5). After he lay with her, David discarded her – she was sent back to her home to await her husband Uriah[3].

Uriah was a man of integrity who refused to go home because he was committed to the leadership expectations of him and would not leave his men for the comforts of home during battle (2 Samuel 11:8-13). David hoped when he sent for Uriah, that Uriah would have slept with Bathsheba, accounting for the pregnancy she revealed to David.[4] When Uriah does not have intercourse with Bathsheba on his return from the battlefield, David covers his misdeeds by killing Uriah. He goes as far as having Uriah hand deliver the letter with the details of the plans David sent for Uriah’s murder.

David goes to great lengths to get what he wants, sacrificing those closest to him. No one is spared his toxic machinations. The women, his soldiers, and his top leaders are all expendable as David focuses on what he wants rather than on the common good (2 Samuel 11:14-25). David’s behaviour and lack of integrity are in opposition to that of Uriah. Uriah, a man of integrity, is killed because he will not conform to the expectations of David’s toxic values.[5]

Bathsheba’s story and her experience with David is overshadowed by David’s story. God sent Nathan the prophet to chastise the king for the wrongs he committed against Uriah and Bathsheba (2 Samuel 12:1-12). Her story is consumed by David’s cry before God in Psalm 51 – which is introduced with the following words in multiple versions of the scriptures: “Prayer for Cleansing and Pardon . . . A Psalm of David, when the prophet Nathan came to him, after he had intercourse with Bathsheba.” In the ensuing verses, David admits to having wronged God and no one else (v.5) yet seeks absolution from bloodguilt (v. 14) and asks that God hides God’s face from David’s sins.

Bathsheba and David married. She lived in his house; one of eight wives David is said to have married.[6] Their first child died. She later gave birth to Solomon. Her silence is deafening. What would Bathsheba have to say?

The toxic masculinity evidenced in David’s house extends to his sons and his daughter, a new generation of men being raised in the silence of David’s house and another generation of women abused by this toxicity.[7] According to the scriptures, David had 19 sons and one named daughter. One daughter – Tamar whose reality as David’s one female child is caught up in the dysfunctional masculinity in this house. Tamar is raped by her half-brother Amnon despite her pleas and her attempts to name the wrong he was about to commit against her.

She even recommended that he ask David to give her to Amnon in marriage (2 Samuel 13:1-22). Tamar’s options were dire. In the moment of violence, she offers herself as her rapist/half-brother’s bride, in keeping with Jewish law (Leviticus 27:3). In the aftermath, “When King David heard of all these things, he became very angry, but he would not punish his son Amnon, because he loved him, for he was his first born” (2 Samuel 13:21). David gives no consideration for his daughter, instead, he opts to support the actions of his son, the first born.[8] More silence in David’s house.

Outside the house, Tamar’s brother Absalom (David’s 3rd born son) seeks vengeance and vows to kill his brother Amnon, further silencing the voice of Tamar in the process. Absalom is more interested in fighting with his brother, rather than attending to the needs of his sister. He tells her: “Well my sister, keep quiet for now, since he is your brother. Don’t you worry about it” (2 Samuel 13:20). Absalom silences his sister, diminishes the experience of Tamar, “reinforces her shame and banishment from the social order”[9] and covers up the actions of his brother. He uses the occasion to assert himself in the power dynamics of the house of David. More silence and violence in David’s house. What would Tamar have to say?

The Voices

In between the experiences of these two women in this house of men, the prophet Nathan visits (2 Samuel 12). His is a defining male voice, cutting into the abuse and toxicity, bringing a spiritual and moral voice into the house of David. Nathan’s voice is also the voice of the community.

There are those who witness the malevolent behaviour and outcomes wrought by abuse and greed, especially from places of power and dare to speak truth to the powers that be. Nathan cuts through the silence of the house, coming from the outside to speak to David. He identifies the abuse of power with boldness and courage.

These three voices – Nathan, Bathsheba, and Tamar – pierce the silence in David’s house. They challenge the narratives and invite scrutiny into the power, wealth, greed, and layers of privilege present in the house of David. They also challenge David’s claim of aloneness in the wrong he did. His actions have ramifications which affect family and the larger community he leads.

The text in our context

We give voice to Bathsheba and Tamar as they join Nathan to speak to the pain of the house of David. The three bringing hope, possibility and change for cultures of rape and violence, and the societal power structures and privilege which create and sustain these toxic cultures.

Bathsheba’s Lament: Her Response to Psalm 51:1-17

Written by Karen Georgia A. Thompson

Have compassion on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love,

according to the abundance of your mercy.

I cry out to you,

make visible and plain

these transgressions inflicted upon me.

O God, will you heal me?

Wash me thoroughly from the stench of shame,

cleanse me from the deep raw wounds on my body and spirit

remove the staining of unwanted touches,

wash away the trauma coursing through my veins,

cleanse the dirt of sexual violations from my body,

remove the violence of abuse and suffering.

Speak to me O God, am I not your child?

They infringed upon my rights,

negated my humanity with both fists,

they violated my trust,

forcing me to hide my face in humiliation,

while they stand before you crying for your help,

asking you to forgive their iniquity and their transgression.

See the bruises God, what about me?

I know their transgressions,

their sins are before me daily

they ignore me as they sit before you weeping

calling me a liar while spinning tall tales of love for me

they ask for your forgiveness,

they should ask of me the same.

Will you seek judgement for me, O God?

Against me they have committed this wrong,

yet they run to you,

trampling my dignity once again

denying to me the power of my choice,

as they return to my bed over and over again

never asking my forgiveness, their lips dry with no apology.

Why listen to their pleas, when they have no truths for me?

You say you desire truth flowing from the inward being:

I was born innocent, a whole person when my mother conceived me

my heart was created clean

my spirit was new and right within me

their violations of my body, their abuse of power

their bruising of my spirit, their killing of my husband

I am broken in body, mind and spirit.

Who will cry with me, O God?

They have done evil in your sight, yet there is no justice,

all watch as they cry claiming their hurt as primary,

communal tears mask the silence of violence,

do not hide your face from their sin

account for their iniquities

they cannot be easily absolved.

O God, will you wash away my pain?

Purge me from the visions that linger,

grant me peace to sweeten this bitterness boiling in my body,

open my lips and my mouth will lambaste this system

uncovering the prevalence of rape, violence, and bloodshed

hold me in your presence, fill me with your Spirit

restore to me the joy of my humanity.

I am broken in spirit.

© Copyright 2022 Karen Georgia A. Thompson. All publishing rights reserved. Used with permission of the author.

Nathan Speaks

“Nathan said to David, “You are the man! Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: I anointed you king over Israel, and I rescued you from the hand of Saul; I gave you your master’s house, and your master’s wives into your bosom, and gave you the house of Israel and of Judah; and if that had been too little, I would have added as much more” (2 Samuel 12:7-8).

Tamar's Plea

Written by Nicole Ashwood

Was this what you meant Mama Bath; when you warned me to watch out for the men in this family? When you told me to cover myself and avoid being alone at any time?

Did you sense that he would tear me apart body and soul with his treachery? Did you know he had been watching me even when I thought I was in the privacy of my room, far away from prying eyes? That whatever he discussed would not be denied?

Could you have guessed that my admonition was for naught? That no one would care that I was caught; trapped in the clutches of my half-brother, who discarded me having used me for his lover?

Did you cry out too, Mama Bath, when the king sent for you, defiled you and sent you home, hoping in vain – that you'd bear no shame, for his indiscretion? And when that shame grew, what was it that moved you to action?

You married him, became his consort, and lived "happily ever after"; when the birth of your firstborn ended in disaster. Were you truly happy, my other mother?

Who is it that spoke for you – were there whispers, looks of scorn, or simply glances of admiration? For finagling the king's undying attention.

Yet you mourned Uriah's death, your husband the warrior, killed for being cuckolded while serving with honour. Did you mourn for the old you, innocent and free? Tell me Mama Bath, do you mourn now for me?

I heeded your words, did what you said, and in spite of my efforts, I'm as one already dead! How did you survive Mama Bath, were there any more tears? Or has your heart been embittered for all those years?

Who spoke for me to the King, Mama? Or is he really unaware that his son – my brother – defiled and abused me without even a care? Where is he, my father, the sire of your son? I'm told he already willed him the kingdom.

Is it enough recompense dear Mama, that he's given the throne, made him his heir over all those other sons? Did that appease you Mama, or did you advocate on my behalf, for sitting here with my shame has torn me apart.

Help me Mama Bath . . . Help! Help me please.

Assure me that this is all a bad dream. Help me? Hhhelp!

© Copyright 2009 Nicole Ashwood. All publishing rights reserved. Used with permission of the author.

What Do We Have to Say?

Adelman contends that although Tamar is left “desolate in her brother’s household, Tamar is the only woman who voices resistance to sexual violation, and so continues to present a powerful example of protest for women today.”[10] The church can no longer ignore the truth of David’s life. If the church is to be a part of changing the experiences of women and provide safety for women to live in freedom and dignity, then David’s truth will need to be named. Recent events across the globe insist that there is need for immediate corrective action, rather than silence that seems to cover up or condone sexual abuse and exploitation. David abused Bathsheba in a power-over dynamic where his power as the King was coercive. This was not a relationship borne out of mutuality and common interest. David saw her and sent for her. He brought her into his house because he lusted after her. What would you say to David about his behaviour with Bathsheba? How can the truth be preached about texts like these?

“All my life I had to fight. I had to fight my daddy. I had to fight my brothers. I had to fight my cousins and my uncles. A girl child ain't safe in a family of men. But I never thought I'd have to fight in my own house…” Alice Walker, The Color Purple. This quote from The Color Purple by Alice Walker identifies the challenge for Tamar and others who are raised in homes where they are not safe. How would you connect this quote from Alice Walker with Tamar’s experience?

Questions

We often say, “silence is violence.” How is violence perpetuated in the silence in David’s house?

How can we challenge notions of toxic masculinity in the church and in society?

Where in the Bible do we encounter silence given to the experiences of women?

Where do we see stories of toxic masculinities in the Bible where the experiences of women are dismissed in the preaching of these stories from the pulpit?

Activities

Bathsheba and Tamar were both victims of dynastic abuse. Does such violence exist in your context? How might you help to challenge the systemic violence that engenders such behaviour? Consider speaking out against such behaviours and establishing/joining victim support programmes.

Prayer

Redeeming God, In a time when sexual exploitation and abuse seem to be so normalized that even the church seems immune to the cries of Bathsheba and Tamar, in a time when #MeToo, #ChurchToo and #ThursdaysinBlack seem not to reduce the 1 in 3 women who face rape and other forms of violence in their lifetime; We ask You to help us exorcise the demonic silence that seems to wink at toxic behaviours. Help us speak out and speak up, even when the perpetrator is our brother, cousin, father, pastor. May Your justice prevail over the complicity in our midst we pray, in Jesus’ name. Amen

Short Bio of Writers

Rev. Dr. Karen Georgia A. Thompson is the Associate General Minister (AGM) for Wider Church Ministries (WCM) and Operations in the United Church of Christ and Co-Executive for Global Ministries with the United Church of Christ and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). She is an inspiring preacher and theologian, who shares her skills and gifts in a variety of settings nationally and internationally, often using her poetry as a part of her ministry. Born in Kingston, Jamaica, her poetry and writings reflect her Jamaican heritage and culture as well as the traditions and lore of her Ancestors.

Rev. Thompson provides leadership for the joint United Church of Canada and United Church of Christ committee working on the United Nations International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024) and continues to be an advocate and activist on global racial justice issues and concerns and is a strong proponent for human rights. She has provided ecumenical leadership within the World Council of Churches (WCC) on the Central Committee and as a Thursdays In Black Ambassador, the Joint Working Group with the Roman Catholic Church, and the Commission for Education and Ecumenical Formation.

Rev. Nicole Ashwood is programme executive for Just Community of Women and Men, World Council of Churches.

[1] New Interpreters’ Bible Commentary 2 Samuel 11 :1-27 Commentary p. 1283.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Wilda C Gafney notes that Bathsheba is obliged to send word to David of her pregnancy, which suggests that she has not seen him, perhaps since he sent for her. Womanist Midrash; A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne, ch 8 p 216

[4] The commentary refutes Randall Bailey’s theory of this act being a political marriage or justification of Solomon as heir, by noting that David’s persistence in covering up his deeds indicate the incredulity of theorizing that this story is solely about legitimizing Solomon’s ascendancy to the kingdom. P. 1285

[5] P 1287

[6] In the chapter, ‘Dominated by David’ Wilda C Gafney argues that David was affiliated with “ten named individual women,” not including “two different groups of women whose numbers and name go unrecorded.” in Womanist Midrash; A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne ch 8; p 203.

[7] Rachel Adelman, in her overview of David’s toxic household situation after the rape of Bathsheba, asserts that in the recounting of Tamar’s rape, “David is strongly implicated in his daughter rape, passively indulgent of his sons, who mirror and amplify the sins of the father.” The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women Tamar 2. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/tamar-2 retrieved June 12, 2022.

[8] Martina Keast argues that David was unable to ‘deny Amnon’s violation because he did not deny himself several times- with Bathsheba and his other wives Exegetical Paper: 2 Samuel 13:1-22 p. 16 in Partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Course TS 601 Scripture Project 1 https://www.academia.edu/36360997/Exegetical_Paper_2_Samuel_13_1_22_Amnon_and_Tamar September 18, 2017; retreived June 12, 2022

[9] Adelman ‘Tamar 2’.

[10] Ibid