The incredibly complex issues that came to the fore in the 1991 WCC Canberra Assembly continue to echo in contemporary ecumenical history.

In 1991, I had been in ecumenical work already sixteen years. I began my ecumenical career being in charge of the WCC relationship with the United Nations. But nothing could have prepared me for my Canberra assignment given by General Secretary Emilio Castro on behalf of the Executive Committee: to enable the membership of the China Christian Council (CCC) by resolving the condition it placed on the WCC.

The condition was that my church, the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan (PCT) should change its name so it would read: the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, China.

The major question in Canberra was whether any church had the right to set preconditions for its membership in the WCC. The condition set by the CCC begged the question of how or whether the WCC and the fellowship of churches could facilitate a true pilgrimage of justice and peace between the PCT and the CCC on the one hand and between the ecumenical family and these two churches, on the other.

An equally significant issue was the profound meaning of the ecumenical fellowship. In John 17:11 Jesus prayed, “Holy Father, protect them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one, as we are one. …may they also be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me.” (John 17:22). Clearly, when the body of Christ is alienated or separated one from another, it is a scandal in the world. Nor does it bear witness to the Biblical injunction.

A third theological challenge comes from Ephesians 2:17-22. What does it mean that all churches are members of one household of Christ and are no longer strangers to our Saviour and to one another? For Christ is our peace and has broken down all the walls of division.

How can the WCC member churches affirm that they belong to Christ across political, ideological, ethnic, cultural divides?

A fourth critical dimension of ecumenical fellowship is that of accountability to one another because of our common faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. Surely, this accountability to one another as members of the body of Christ applies regardless of differences and differing perspectives.

The WCC member churches cannot shirk their responsibilities but must confront their accountability to any church confident that the Holy Spirit shall intercede however intractable or insurmountable are the walls of division.

The CCC request to the WCC was unprecedented and was the culmination of three years of confidential discussion between the WCC and the CCC. Two key developments since 1979 generated an immense ecumenical interest to see the CCC join its fellowship. The first was the opening up of China in the 1970s that enabled the Christian community to participate in a meeting of the World Conference on Religion and Peace in the United States in 1979.

This marked the first official participation by the church in China since the 1960s in an international religious gathering, thus portending the possibility for the CCC to join the WCC.

The second was the establishment of the China Christian Council in 1980, as a post-denominational official church body that merged the various denominations, even though its predecessor body, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement would co-exist side by side.

In 1986, the WCC decided officially to recognize the CCC and the Amity Foundation as its partners in China. This was a highly controversial decision as many people within the WCC lobbied actively that the WCC should not take such an action because they feared that the China Christian Council was controlled by the government.

It was therefore “public” knowledge that the CCC would join the WCC at the Canberra Assembly provided that there would be no official listing of Taiwan or Hong Kong as separate countries and provided that the PCT change its name.

In response to an enquiry from the WCC about the view of the PCT regarding CCC membership, the PCT replied in January 1991 that it would welcome the membership of the CCC as long as its application fulfills WCC membership requirements and provided that it would not “result in detriment, loss of dignity or loss of privilege of any member.”

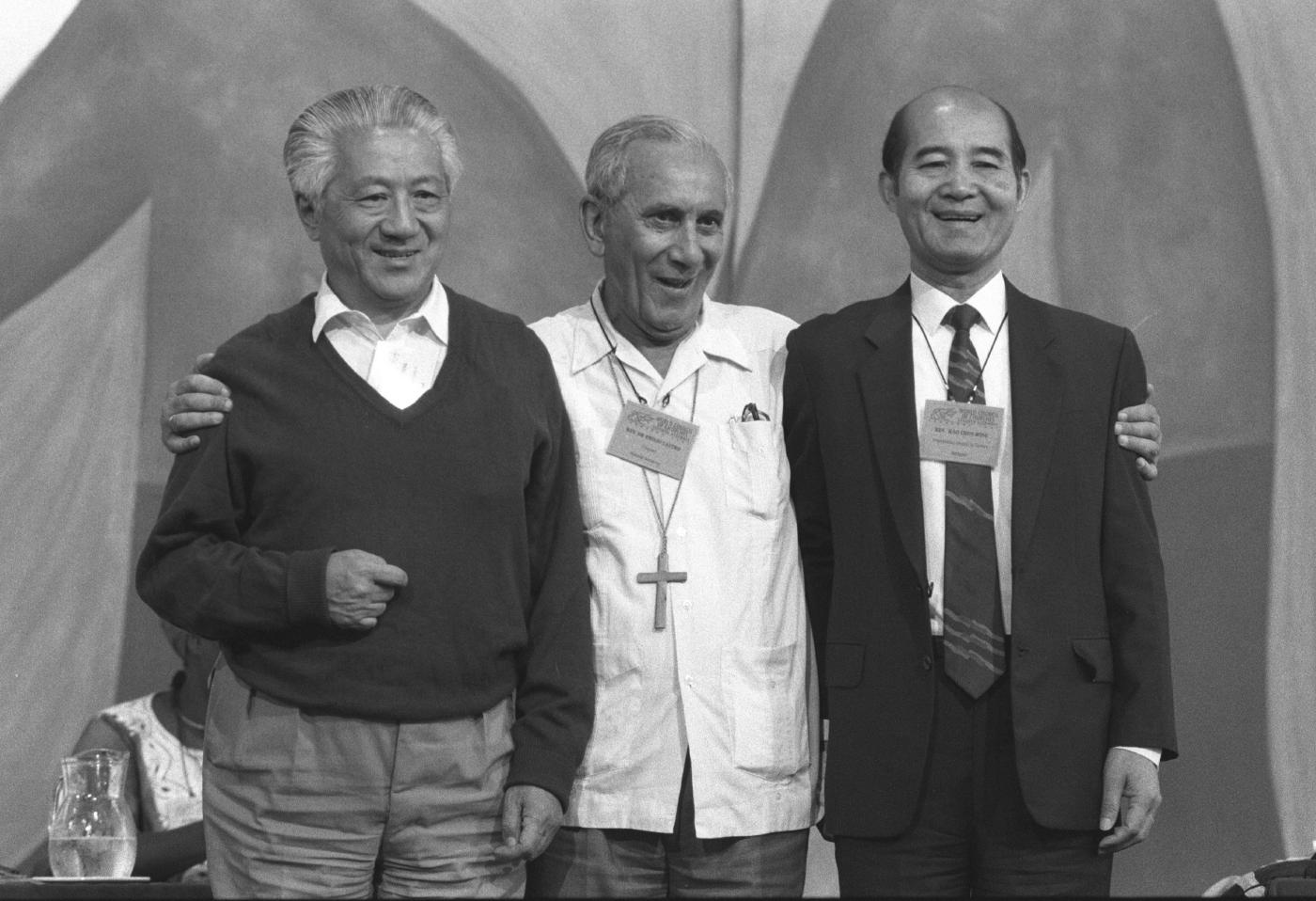

This was the backdrop of my assignment in Canberra as I “shuttled” back and forth between the two delegations. Assembly participants were intensely interested in the outcome, as the Assembly Daily carried interviews with the principals of each church, General Secretary C.M. Kao for the PCT and Bishop K. H. Ting for the CCC.

After ten days of negotiations, during which the church leaders from around the world had occasions to meet with the delegations separately to encourage them to come to a satisfactory resolution, a happy resolution was reached: the CCC agreed to drop its demand while the WCC would list its member churches only in alphabetical order and that it would uphold its one-China policy.

The WCC agreed to write a letter to the CCC expressing this agreement. This was dated February 20, 1991, the last day of the Assembly, and it enabled the CCC to become the 317th member church. The two delegations were welcomed on the stage and Bishop Ting’s words on the significance of its membership were recorded in the official minutes of the Canberra Assembly:

“Our membership will in no way impair the independence and integrity of any church outside mainland China.”